Have you ever considered the importance of iron? I have – and it’s not just because I’m Scottish and have a patriotic love for Irn Bru… I’m interested in the iron contained in glacial sediments, and how this iron can help to feed the world’s ocean and lock away atmospheric CO2

We know that there’s iron in spinach (thanks Popeye) and in the fizzy ginger delight of a can of Irn Bru but did you know that rocks and sediments in Antarctica contain iron too? Whilst geologists have spent many, many years studying the chemistry of rocks all over the world, we’ve not been working in Antarctica for long enough to really explore the iron content of Antarctic rocks. That’s because we didn’t know that Antarctica existed for much of human history, and when it was first sighted, just 200 years ago, we soon realised just how hard it is to get there, and later, how hard it is to work in the worlds’ most extreme continent on Earth – where temperatures plummet to -80°C and winds often exceed 100 mph.

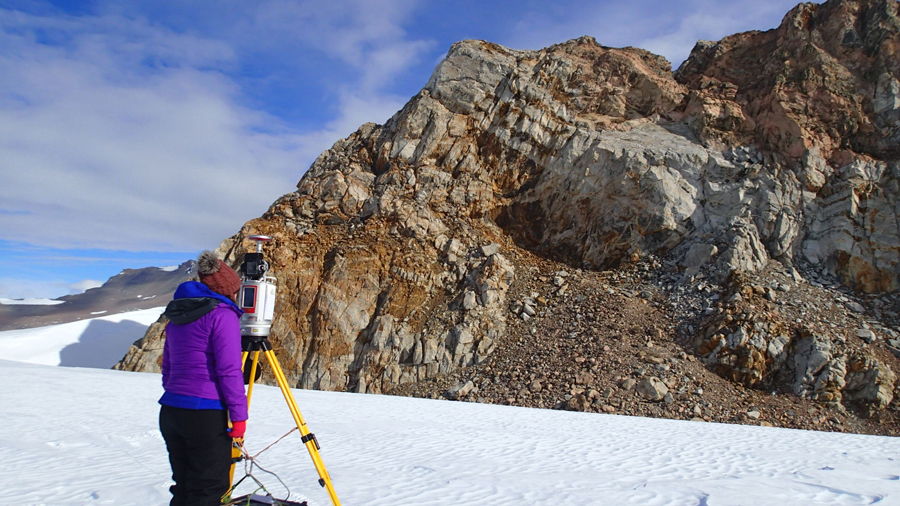

Photo credit: Kate Winter and the International Polar Foundation

As a trained geologist and glaciologist (combining my passion for rocks and ice), I’m trying to trace Antarctic iron from source to sink. I use terrestrial laser scanners, drones and seismometers to monitor the mountains that poke up above the thick Antarctic ice sheets, to record how frequently iron-rich rocks crumble and fall into the vast Antarctic ice sheet below. With two pairs of gloves on, to keep my hands toasty at -18°C, I collect rock samples from the mountains around the coast of East Antarctica. I scoop up piles of loose sediment that accumulate near the mountains in moraine deposits and I scoot around on my snowmobile to pick up some of the more sporadic rock samples which are dotted across the ice sheet as a result of complex ice flow processes.

We store these sediments in small vials in the huge walk in freezer at the Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Research Station so that they are perfectly preserved in their frozen state. At the end of our field season, when the sun begins to set in Antarctica at the end of February and the summer scientists have to leave the continent, we pack up our samples and return them to Newcastle by ship or air, so that the real detective work can begin.

Photo credit: Kate Winter and the International Polar Foundation

In the warmth of the laboratories at Northumbria University, we slowly defrost our Antarctic sediments and run them through a series of tests in expensive machines which spit out values that reveal their unique chemical signature and mineralogical composition. We were surprised and delighted to find iron in every single one of our samples!

When we combine our laboratory analysis with our terrestrial laser scan, drone and seismometer data we can see how frequently these iron rich rocks fall from the steep mountain slopes and enter the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Temperature loggers tell us that these mountains undergo significant temperature changes when the sun shines. Whilst the air temperature is always below 0°C the dark mountain rocks heat up to +25°C when the sun is out! It’s this change in temperature that helps to loosen the rock, and transport iron from the mountains, onto the ice sheet below.

Photo credit: Kate Winter and the International Polar Foundation

This is all very well and good – but you may still be wondering why I care so much about iron. Well, I’m getting onto that! You see, huge ice masses called glaciers gradually flow from the mountains to the ocean that surrounds Antarctica. A journey of many hundreds of kilometres in some places.

We trace this epic journey with ice penetrating radar. It’s a technique that works a bit like an X-ray, allowing us to peer-beneath the surface to see what lies beneath. By towing our radar across the ice behind a snowmobile we can trace the transport pathways of iron-rich sediments.

Once the sediments enter the ocean they rain out of calving icebergs. This delivers nutrients to the Southern Ocean, which is nutrient-rich but iron-limited. These inputs of iron yield huge phytoplankton blooms around the coastline of Antarctica which we can see in satellite imagery. As phytoplankton are the base of several aquatic food webs, these blooms kick start one of the most impressive and important food chains on our planet. One which draw down atmospheric CO2 in the shells of organisms, locking it away it in our oceans.

Now that is cool!

Photo credit: Kate Winter and the International Polar Foundation

This science is really new, so we’re still exploring how much iron is transported through glacial systems in Antarctica and the impact this has on life in the Southern Ocean and the global carbon feedback cycle, but one thing is for sure – iron is a catalyst for life, and it is incredibly important – not just for the Irn Bru making process!

Ever considered?

If you’d like to be an Antarctic researcher like Kate, you’ll need to work hard at school, and study a relevant subject at University. After you complete your degree, there are so many jobs you can do in Antarctica! You can engineer renewable energy systems that work in the cold, you can be the architect that designs new research stations, you can be a naval engineer and work on the Antarctic research ships or you can be a scientific researcher – exploring vast topics such as the atmosphere above Antarctica, meteorite deposits that accumulate on the continent, ice flow processes and Antarctic biology. Whatever you are interested in, you can do it in Antarctica! That way you will have a job that allows you to learn about one of the most amazing continents on Earth and explore a region of the world that very few people get to visit. It’s quite a privilege.

Download PDF

If you wish to save, or print, this article please use this pdf version »