Just below the low tide mark there are seagrass meadows. Even if you have been to the seaside, you might never have seen them. These meadows are fantastic nurseries for little fish and draw down more CO2 per hectare than rainforest. This is a story about scientists sowing new seagrass meadows.

When Queen Victoria was a young queen every estuary in the UK was full of seagrass meadows. In these meadows the fish we like to eat, like cod, plaice, and herring, can feed and hide from predators.

The meadows also provide food and shelter for beautiful creatures like seahorses, cuttlefish, stalked anemones and coloured snails.

The meadows trap floating particles containing carbon and capture carbon dioxide during photosynthesis. This can draw down and store 500 kg of carbon per hectare of seagrass per year. This is more than ten times the carbon absorbed by the same area of UK forest.

While seagrass covers just 0.2% of the ocean floor it holds an estimated 10% of all the carbon stored under the waves. Today though, there is much less seagrass than there used to be: perhaps only one twentieth (5%) of the seagrass meadows there was in the UK seas when Queen Victoria was alive. One reason there is much less seagrass is that in the 1930’s a disease destroyed an estimated 50% of the meadows. This disease was a natural disaster. An unnatural disaster, untreated sewage and farm run-off destroyed even more by causing eutrophication.

Raking up seagrass for replanting, Denmark, summer 2020. Photo courtesy of Troels Lange, University of South Denmark

The problem with the untreated sewage and the fertiliser farm run-off is that it causes a huge increase in plant nutrients. The sewage breaks down releasing nutrients, such as nitrates and phosphates and the fertiliser run off from farms adds even more to the nutrient concentration. The high nutrient concentration in turn increases the growth of algae causing algal blooms. The algae float above the seagrasses reducing the light available for seagrasses to photosynthesize.

Later the algae then die and rot. The bacteria rotting the algae use up all the oxygen in the water. The loss of light combined with the oxygen stress can kill the seagrass.

Unfortunately, the estuaries where seagrass live are also the estuaries down which rivers bring our filth, but around thirty years ago laws were passed to reduce this pollution by improving the treatment of sewage. Now many of the places on the seashore where seagrass used to live are clean enough to support seagrass growth again.

As seagrasses are flowering plants (angiosperms), they make seeds. These seeds float in sea currents and many of them are eaten, for example by crabs, so the chances of seagrass naturally re-establishing from surviving patches many miles away are remote

Therefore, scientists are trying out different restoration techniques as they want to jump-start the recovery.

In Wales scientists from Swansea University have asked volunteers to collect a million seeds from places as far apart as the Scilly Isles and Anglesey. These seeds are placed with some sand into little hessian bags – junior school students have helped with this. The bags are strung together and weighed down at each end. The whole seeding structure is dropped onto the seafloor. As the seeds germinate, they grow through the hessian bag. The bag harmlessly rots away. This approach has been used to grow a few hectares so far.

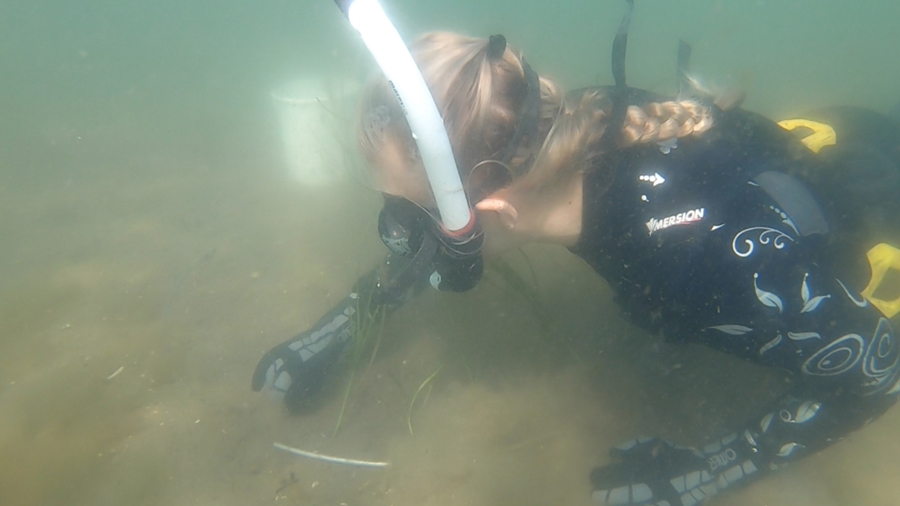

Replanting seagrass, Denmark, summer 2020. Photo courtesy of Troels Lange, University of South Denmark

In Denmark scientists from the University of South Denmark are using a different approach. Here they are raking up shoots from dense patches of seagrass. They sort out the shoots and tie each shoot onto a nail. Shoots and nails are planted directly into the seabed where the weight of the nail holds the plant in place until its new roots take over. This approach has been used to grow a few tens of hectares so far.

In the US there has been one spectacularly successful project. In Chesapeake Bay seeds have been collected and broadcast sown, basically just thrown out from a boat. For around 20 years. 74.5 million seeds were broadcast into 536 individual restoration plots totaling 213 hectares. So far sowing seeds in this way has resulted in a total of 3612 hectares of meadow in an area that had virtually no coverage before the restoration.

After a few years of not much happening new patches started to grow and these are now spreading by themselves. They now cover roughly 15 times the area originally seeded. As the seagrass has come back, so have other wildlife including bay scallops (Argopecten irradians) which are a commercially important shellfish.

Now scientists have shown that restoration is possible the next step is to find funding for the work to be scaled up. All the restoration approaches are very labour intensive and so expensive. Fortunately, it looks like we do not need to replant every hectare lost to pollution and developments such as boating marinas.

But we do need to kick-start growth in scores of places so that seagrass meadows can again be found in every estuary and sheltered bay around the UK.

This needs money and so our politicians must be persuaded that bringing back seagrass for wildlife, fishing and drawing-down carbon is worth it.

Meanwhile you can help by volunteering to collect seagrass seed at the seaside through Project Seagrass.

Download PDF

If you wish to save, or print, this article please use this pdf version »

Learning resource

We have created learning notes to assist students and educators to further investigate the topics covered in this article. You can download the learning resource here »