Malaria is a life-threatening disease transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes that affects millions of people worldwide. Here we provide an insight into global malaria importance, why mosquito control is essential and how it can be performed, focusing on more recent and innovative strategies based on genetic approaches.

Mosquitoes are described as one of the most dangerous animals, but they are not harmful by themselves. The real problem is the wide variety of pathogens – viruses, bacteria, and parasites – that female mosquitoes can transmit when they bite. Only the females bite since they use blood nutrients to develop the eggs that they will lay a few days later.

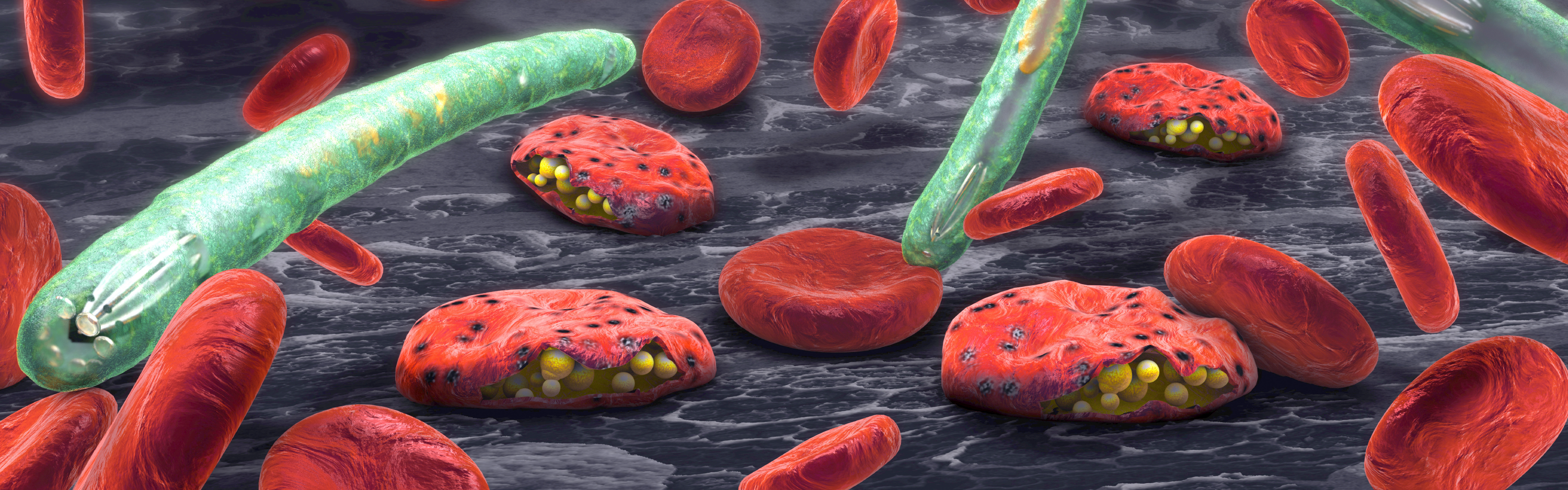

The most threatening parasite disease spread by mosquitoes is malaria, caused by parasites called Plasmodium. Five different Plasmodium species can affect humans, and they are transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes. The severity of the disease depends on the Plasmodium species and the immune condition of the person. According to WHO reports, this disease is endemic in more than 80 countries, most of them in Africa. They have also reported 229 million cases and around 400,000 deaths in 2019. This data clearly shows the urgency for developing control strategies to manage and decrease malaria incidence in these countries.

There is no vaccine for malaria, even after years of research. Different approaches have had some success but are not effective enough. Plasmodium is a very complex parasite, elusive and with an intricate life cycle that involves various stages and at least two hosts, the human, and the mosquito. These are the reasons why controlling malaria does not rely on a unique method or strategy. Several points are crucial to controlling the spread of the pathogen:

- Early diagnosis. Rapid and early diagnosis techniques mean that people are treated before they develop severe symptoms and can avoid a high number of deaths. Nowadays, different rapid diagnostic tests that are easy to use are available and have had a high impact in endemic countries.

- Treatment. Effective drugs have been developed and used over the years like chloroquine, artemisinin, or combinations of artesunate-sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine.

- Social and infrastructure improvement. Educating people on how malaria is transmitted and what they can do to prevent transmission through infrastructure improvement. Campaigns can help with this. Better housing would prevent mosquitoes from entering the buildings and biting, reducing disease transmission.

- Stop transmission from mosquitoes to human. This can be achieved by controlling the mosquito population and placing barriers that avoid mosquito-human contact. The most common system is extensive insecticide spraying to reduce mosquito density. Also bed nets are widely used to prevent mosquito bites whilst people are sleeping. The combination of insecticide and bed-net are insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) and the long-lasting insecticide nets (LLINs) that have had a huge impact on reducing malaria.

These key points have had an enormous impact on the different anti-malaria campaigns performed in endemic countries and have had excellent results. A significant decrease in the incidence and mortality has been reached. However, this decrease has reached a plateau in the last few years, and the existing tools seem not to be so effective anymore. The emergence of resistance from the Plasmodium parasite to treatments and of the mosquito to insecticides have been hijacking the success of the control campaigns. Moreover, the excessive use of insecticide spraying has raised environmental concerns because it not only affects the targeted mosquito, but also other insects, other animals and the environment.

Focusing on mosquito population control, new strategies based on genetic approaches have emerged with the premise of being more eco-friendly. The aim is to not harm the environment or affect other animals since they will only target a specific mosquito species. Genetic control strategies depend on the introduction of an inheritable trait into the wild type population. There are two main outcomes, the suppression, or the replacement of the insect population. In the first one, the new trait leads to a reduction of their population. In the second one, the existing mosquito population is replaced with mosquitoes that have the new characteristic, making the mosquito, for example, unable to transmit the pathogen (refractoriness), the latter doesn’t reduce the number of mosquitoes in the area.

The discovery of CRISPR/Cas9, recently awarded the Nobel Prize, has opened an incredible path in genetics and is the fundamental pillar for the new strategies under development for mosquito control. Specifically, the so-called gene drive systems benefit from the CRISPR/Cas9 technology. These gene drive systems aim to spread the new trait into the population in a super-Mendelian way. It means that the gene drive encourages unbalanced inheritance in favour of the new trait, so the new trait is passed on to off-spring so the new would make the ‘old’ disappear in a short period of time. And, as previously mentioned, these could be by reducing or replacing.

A standard gene drive would spread without limit, but it would be beneficial (although complicated) to control it in a specific area and time period. That is why, nowadays, most of the studies are focused on systems that are self-limited in both space and time. In this way, the genetically modified mosquito released in an ecosystem would affect the endemic mosquito only, reaching the goal of suppression or replacement only for a certain time period and without spreading to other regions.

Of course, these strategies are still under study, and a lot of research is ongoing to optimise these systems. Before going to field release in an endemic malaria region, it would be necessary to perform laboratory cage trials, small and large cage trials in the laboratories where we can see if the system works on a small scale, followed by field-controlled trials. These last kinds of trials are performed in closed field facilities with important security measures to avoid release into the wild, but at the same time, they can be used to mimic how the system would work in a highly accurate way.

We need to keep in mind that genetic control tools are not meant to be the final and only solution for mosquito-borne diseases, rather they are another instrument to be used in this fight against the transmission of diseases as harmful as malaria. The combination of early diagnosis, successful treatments, sanitization, house improvements, hopefully, an effective vaccine and, of course, an efficient mosquito control strategy would be the way to stop the transmission of the Plasmodium parasite.

Download PDF

If you wish to save, or print, this article please use this pdf version »